Walking down the narrow corridor towards stylist Harry Lambert’s studio, I can’t be the first person to wonder if Harry Styles – Lambert’s most famous client – has trod the same blue carpet. Not that Lambert would tell me. Getting him to talk about Styles is like getting blood from a stone. “OK, look,” he says. “When it comes to questions about Harry, I just consider our relationship too private to go too deep. You have to remember I am there in the most intimate times with people I work with. I’m often the last person they see before they go on stage. It’s an intimate space! I’m aware that a lot of the attention I get is because of him, but I want to be very careful. But let’s try. OK. Go.”

Harry met Harry around the time of One Direction’s 2014 album, Four. Rumours of a solo career were circulating, and Styles was going through his “Jagger period”, wearing black Saint Laurent suits, Chelsea boots and leonine hair tamed by bright bandanas – fashion filtered through NME rather than GQ.

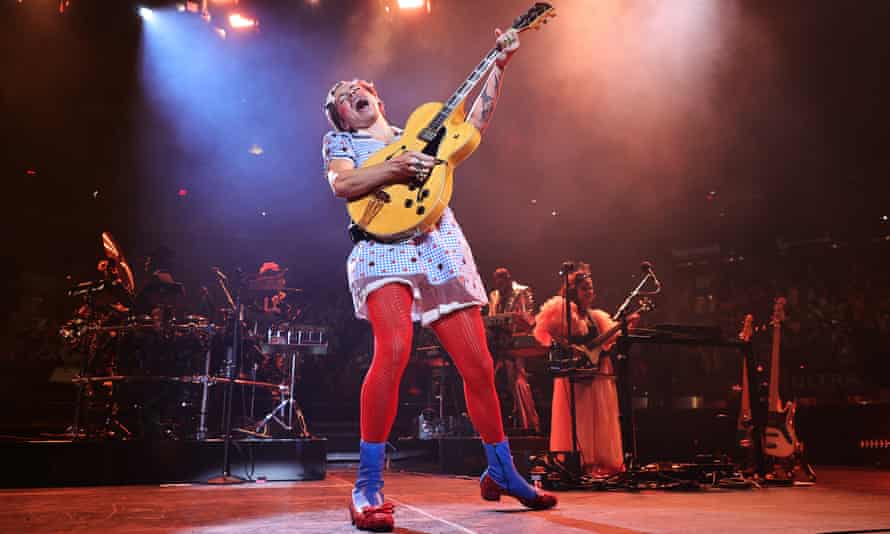

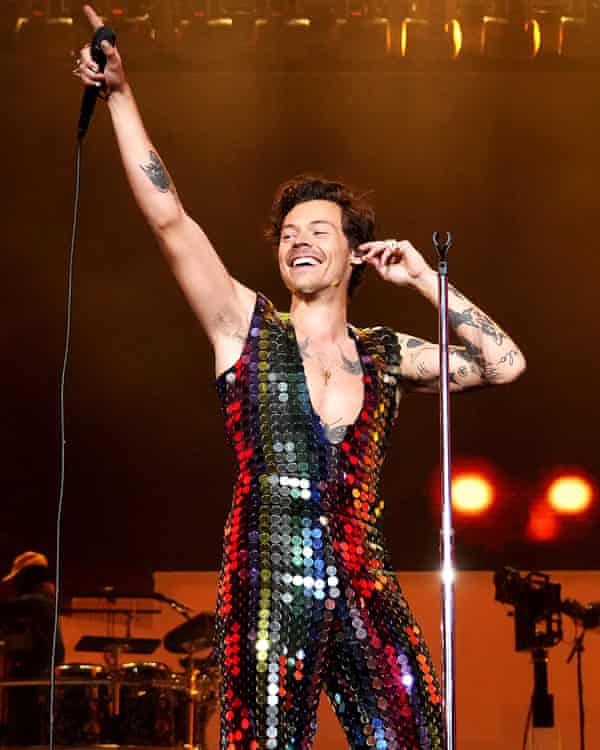

Lambert was mostly styling magazine shoots and fashion shows when they were introduced to each other. He presented a wardrobe (“playful stuff, Gucci and JW Anderson, stuff like that”), and Styles agreed to give it a whirl. What emerged is best described as 1970s man, resurrected – flares, with a side of camp. Styles was always game, he says, “but when it happened, it was still like: ‘Fuck, this is wild.’”

The fashion industry gobbled it up. From the sheer black blouse and single pearl earring at the 2019 Met Gala, to the tight crimson Arturo Obegero jumpsuit in the video to As It Was, Styles became mainstream pop’s most determined subverter of gender stereotypes.

Lambert has been central to this, a sort of Thomas Cromwell to Styles’s Henry VIII, but dissolving binaries instead of monasteries. Not that that’s how he sees it: “Look, when it comes to this [gender stuff], I wish I could be all: ‘I wanted to change the world!’ But it’s more that it’s a byproduct of what we’re doing,” he says. “If you look at pop icons over the years, fashion is such an integral part of their image, like Björk in the swan dress, Britney in the schoolgirl outfit. I’m aware that what I do is having an impact, but is that top of the agenda for me? No.”

We’re sitting on a bench in the communal garden behind his two-room studio in Hoxton, east London. In one room, platform shoes spill out of an Ikea Kallax unit. In the other, rails of clothes sit. Lambert, 35, is warm and chatty, with a gentle East Anglian accent and short bleached hair. He’s wearing wide-legged Marni trousers in chequerboard brown, large black pearls and a T-shirt lightly stained with breakfast.

Celebrity stylists are relatively new. In Hollywood’s golden age – Lambert’s favourite era – actors were styled by costume designers from the studios. By the early 70s, the studio system was over, so stars dressed themselves, which didn’t always go well (Google any Oscars ceremony in the 1980s).

It wasn’t until the mid-00s and Rachel Zoe – who turned her cadre (Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan) into avatars of her stick-thin self, and is rumoured to have commanded $10,000 a day – that stylists became as famous as their clients.

Today, the red carpet is an economy unto itself, built on the (often false) idea that what celebrities wear is an extension of their personality rather than, say, a mutually beneficial marketing tool brokered between label, celebrity and stylist. No one knows how much money changes hands, but given that many celebrities require stylists as much off stage as on (the walking-to-the-car-holding-a-juice outfit, can be as considered as what is worn to the Grammys) the celebrity stylist has never been more powerful. Which explains why some of the big Hollywood ones – Law Roach, say, who put Zendaya in a hot pink breastplate, or Karla Welch, who put Justin Bieber in extra-long sleeved T-shirts – are household names, if you live in that sort of home.

Unusually for a stylist, Lambert has just four clients: Styles, Everton footballer Dominic Calvert-Lewin, and The Crown actors Emma Corrin and Josh O’Connor (each of whom has a body double who tries on outfits the day before). Lambert gets approached a lot, but usually says no. “I only style people who – sorry to sound all LA – I connect with, or who I can transform. I once styled Kylie [Minogue] – but what do you even do with Kylie?”

It’s reasonable to say that O’Connor’s look is the most conventional. Standouts include a navy double-breasted sailor suit with ceramic buttons by SS Daley, worn to last year’s TV Baftas, “but there’s always a little twist, or flourish”, says Lambert “It can never be conventional – I hate that.”

Corrin, whom he met through a friend, came out as queer last year, and uses clothes to communicate this. “There’s a pressure on girls in acting to be sexy, to be a bombshell, to have [their] boobs out. Emma is sexy, but it’s about playing with people’s perceptions of what is beautiful,” says Lambert. I say the Loewe dress and balloon bra she wore to the Olivier awards in April certainly felt like an in-joke. “The Oliviers are a bit stuffy, so we thought: ‘Let’s do something that most people aren’t going to get,’” he says with a laugh. “It’s a conversation, but in a dress. Even the Daily Mail loved it.”

As with all stylists’ muses, there is an obligation to wear designers if they are linked with them – Corrin was the face of Miu Miu, Styles of Gucci, and O’Connor of Loewe. But in using vintage pieces as well as pushing smaller designers such as Daley, Edward Crutchley and Harris Reed, whose gender-fluid designs have since ended up at the Met Gala, Lambert is attempting to redress the power balance.

Earlier this year, he turned down the chance to appear on the cover of The Hollywood Reporter. “I didn’t get into this job to be on a [magazine] cover. Fashion is scary, fashion week is scary,” Lambert says. “There are ‘faces’, like Anna Wintour, and then there are people like me.”

But because of his job – and because of social media – he is a face of sorts. “Someone took my picture on the bus and tagged me this week. So I’m famous to a particular group of people.” The Harrys have nicknames for each other (Lambert is Susan, and Styles is Sue) and the internet has fun with their relationship, with Reddit threads devoted to to unpacking what these names mean. Again, Lambert won’t comment, but it seems an efficient way to differentiate between two people called Harry.

Growing up in Norwich, Lambert was into clothes, not fashion. He cycled through trends familiar to a millennial (the skateboarding emo phase, the Abercrombie & Fitch ripped loose jeans phase) and, at school, drifted towards art. He studied photography at Rochester University and while he loved the narrative side, he tripped up on the technicalities, and instead spent his summers interning at various magazines.

He then moved to east London, just at the end of nu-rave. “I got into the industry right at the end, just after [the recession], when everyone had money, but also just before styling became a thing,” he says. He got work as a commercial stylist – including a stint at fast fashion “factory” Asos, and later Topman, but his Damascene moment was “bejewelling Little Boots’ roller skates on a shoot”.

His most recent client is Calvert-Lewin, one of the few footballers who doesn’t dress as if he has been vomited on by a bank. Last winter’s Arena Homme+ cover, in which he wears a flared short suit and a glittery pink Prada handbag, was a blue-tick Lambert look – high fashion with an androgynous twist. Is Lambert a football fan? “No. I had to do half a season at Norwich City – Delia Smith’s team – when I was a kid, but only to escort my little brother.”

You only need to look at Little Richard, David Bowie or Prince to see that androgyny has been part of pop since the beginning. Yet in football, outward expressions of so-called femininity are few and far between. Is Lambert trying to drive a conversation about gender by introducing this fashion to the Premier League? Lambert laughs again. “I didn’t bring the handbags to Dominic. He has three or four Chanel handbags of his own. But just because someone is a masculine straight guy in the football community, and has a handbag, it shouldn’t be a big deal.” But it is a big deal, I say, in a good way. “OK, yeah, I understand how toxic the [football] industry can be, so to see a man with a Chanel handbag is … something. But everyone is trying to tap into that market,” he says of fashion and sport. “Back in the day, if you were into clothes you were gay. Now caring about how you look – it’s almost normal.”

It’s unsurprising then that Gucci recently signed pomade-loving footballer Jack Grealish to front a future campaign. At the mention of his name, Lambert shifts around, then denies all knowledge of the signing. I’d put a tenner on him being involved.

“I think how men dress is changing,” he says. “The Loewe aesthetic is going to be the next super-brand for youth in the way that Balenciaga and Vetements [two of the brands responsible for luxury logo streetwear] rewrote what was cool. You can see it happening.” To translate, Lambert means clothes that are pretty and surreal, logo-free knitwear and lots of colour. Like Styles’ famous rainbow cardigan – effeminate and fun. “It’s the vibe shift, yeah.”

“When I’m gone,” Lambert says, “I just hope it’s silly things such as putting Harry [Styles] in pearls and that men can wear necklaces and it not be a thing – that’s the stuff I want to be remembered for. That and when people dress up as Harry for Halloween.” He claps his hands. “It means that we’ve done something that has had cultural impact. It means we’ve got through.”

https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2022/may/26/when-harry-met-harry-the-man-who-put-harry-styles-in-a-dress

fashion rec fashion wanted

fashion rec fashion wanted